The following article is reprinted courtesy of The News-Gazette.

Champaign: The Creation of the City of Champaign

The route of a railroad played a major role in the creation and location of modern-day Champaign.

by Dannel McCollum

Former Champaign Mayor (1987-1991)

The story of the City of Champaign begins at least as far back as the founding of the county and the establishment of Urbana as the county seat. The individual most responsible for the new county was State Senator John Vance, who represented Vermillion County as well as the unorganized areas to the west and north.

Vance determined Champaign County’s borders and provided the names for both the county and its seat of justice. Hailing from Urbana, the county seat of Champaign County, Ohio, Vance did what many others had done through homesickness, nostalgia or lack of imagination, he carried place names with him as he moved west.

When the county came into existence in 1833, the area was a wilderness – 80 percent prairie. The remaining 20 percent was timber, largely along creeks and streams. Early settlers shunned the prairie area, preferring instead to clear timber for their homesteads. The southwest corner of one of these forested areas, Big Grove, was selected as the location for Urbana.

County population growth was slow for the next 20 years, especially in the 36 square mile area that was to become West Urbana and later Champaign Township. The 1878 history offered a brief explanation:

“It was not until after 1857 that the township began to fill up to any appreciable degree. The slow growth previous to that period was no doubt owing to the opinion generally that the prairie was not a fit habitation for man.”

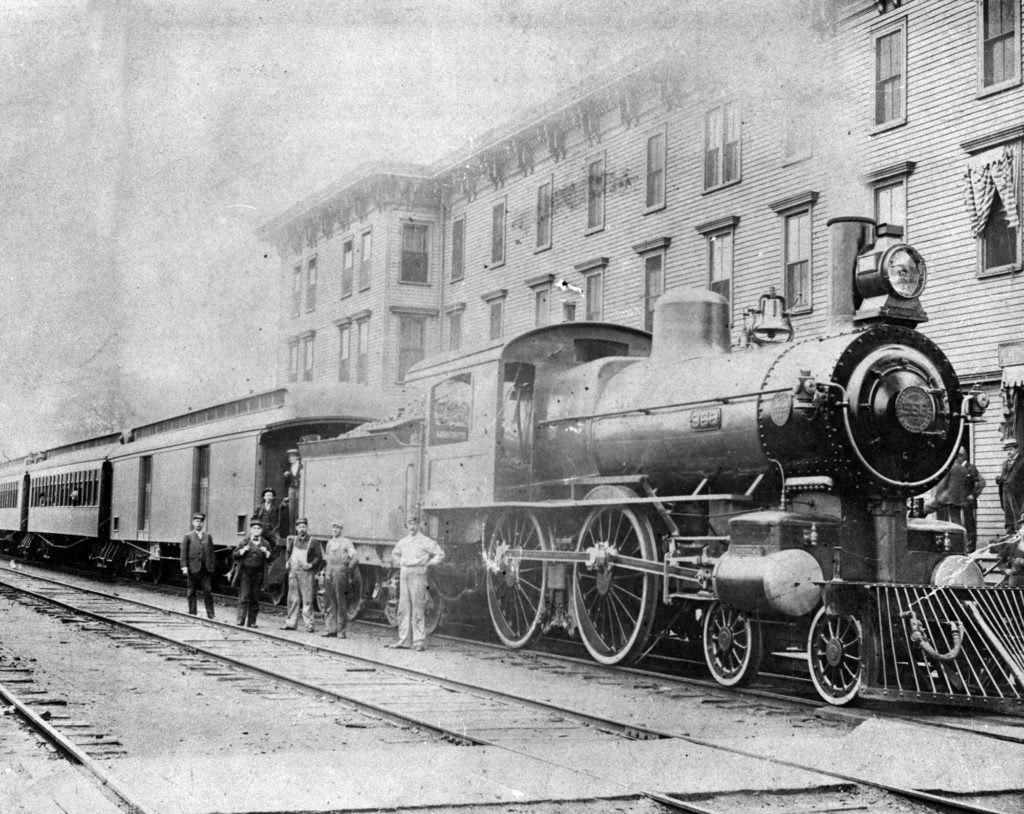

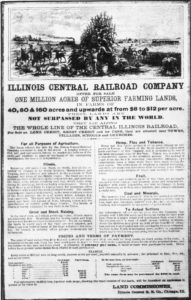

But the days that Champaign County was to remain a frontier backwater were numbered. In 1850, President Pierce approved the land grant for the Illinois Central Railroad. Late in the following year, one of the most massive construction projects witnessed by the young nation was begun. The original main line was to run from LaSalle-Peru to Cairo. The Chicago Branch would connect Chicago via east-central Illinois to the main line at Centralia.

Survey crews mapped four possible routes for the branch across Champaign County, selecting the one which ran across the open prairie two miles west of the Urbana courthouse. J. O. Cunningham, an Urbana newspaperman when the Illinois Central was built, discussed the final choice in this 1905 History of Champaign County:

“Why the westernmost line was acceptable and two towns made possible – if not inevitable – has long and often been misunderstood and-though not intentionally misrepresented.”

Various stories have, in fact, circulated over the years concerning the bypassing of the county seat inputting self-interest to the railroad and stupidity to Urbana citizens. The earliest, absent important details, was related by Lothrop in his first history of Champaign County (1870).

“The purpose of the company building the Illinois Central Railroad was to run the line through or near, the City of Urbana, but owing to some difficulty in procuring the right of way, and lands deemed necessary for the use of the company, that route was abandoned … And thus began Champaign, which but for the unfortunate disagreement between the railroad and the citizens of Urbana, would never have been known.”

A more specific version was related in the 1878 county history:

“The location of Champaign … grew out of a disagreement between Colonel M.W. Busey, owner of a large body of land near Urbana, and the Illinois Central Railroad Company … Col. Busey spent some time in proving that the Urbana line was a better one than the proposed Danville route. His arguments prevailed, and the Urbana line was decided upon and surveyed accordingly. The company asked the Colonel to donate to them 80 acres near (Urbana). He declined to do this, but offered to give them 20 acres for the depot and round-house, and sell 40 acres more at a reasonable price. The officials would not accept his proposition, but threatened to run their line further west, and establish their depot at a considerable distance from their county seat, which was done. Having located their line, the company selected 80 acres as the site for the new town which land belonged to Colonel Busey.”

Both of these stories strain credulity. Probably the most important reason for questioning them is that they do not agree with the version related by Cunningham, who wrote in 1905:

“At the time, economy in the construction of the line was of much greater importance to the company than was the running of the line nearby a ready made town-especially so unimportant as was Urbana at the time.”

Cunningham’s opinion was seconded by Illinois Central historian, Howard Brownson:

“Thus the company selected the route entirely upon its economic and engineering merits and with exceptions, the line chosen was the most direct and shortest of the possible routes.”

An examination of the topographic map of Champaign County would confirm that. The tracks strike deftly across the county along the drainage divide – the Sangamon and Kaskaskia on the west, the Middle Fork, Salt Fork and the Embarrass on the east. Moreover, the railroad owned land on both sides of the right of way and easily could have located the station on its own land. It seems that the railroad would have had a strong predisposition to choose its own land rather than land for which it had to pay, especially land belonging to Busey if there had been a disagreement.

Moreover, Busey was an early promoter of the railroad, both as a member of the legislature, and later as a private citizen. “His services,” according to his biography in Pioneers of Champaign County” (were) invaluable in securing the charter for the Illinois Central Railroad.” Why would Busey have feuded with the Illinois Central, a company he had helped, over so small a matter? Also, Cunningham states that Busey, “was equally interested in the land bordering all of the (proposed) lines.” The latter to gain in either case.

It does seem strange that after not purchasing public lands for almost a decade, Busey made a fortunate purchase of 80 acres through which the Chicago Branch just happened to be built. A supporter of the enterprise, he probably followed events closely and when, in 1848, it became clear Chicago was going to be served by the railroad, he made an exceptionally good guess as to where the line might go.

Busey died on December 13, 1852, but not before he had discussed station sites with the railroad. Just over five months later, his son-in-law sold the strategic 80-acre tract to the Illinois Central for the princely sum of $1,600. (Public land, where available in the area, was priced at $1.25 per acre, so Busey had paid only $100 for the land in question less than five years earlier.)

Today, the Busey tract is defined by Springfield Avenue on the south, Washington Street on the north, Neil Street on the west and First Street on the east. By July 1853, construction crews had begun erecting depot buildings on the northern portion of the holding – the first buildings of any sort in the future city.

Today, the Busey tract is defined by Springfield Avenue on the south, Washington Street on the north, Neil Street on the west and First Street on the east. By July 1853, construction crews had begun erecting depot buildings on the northern portion of the holding – the first buildings of any sort in the future city.

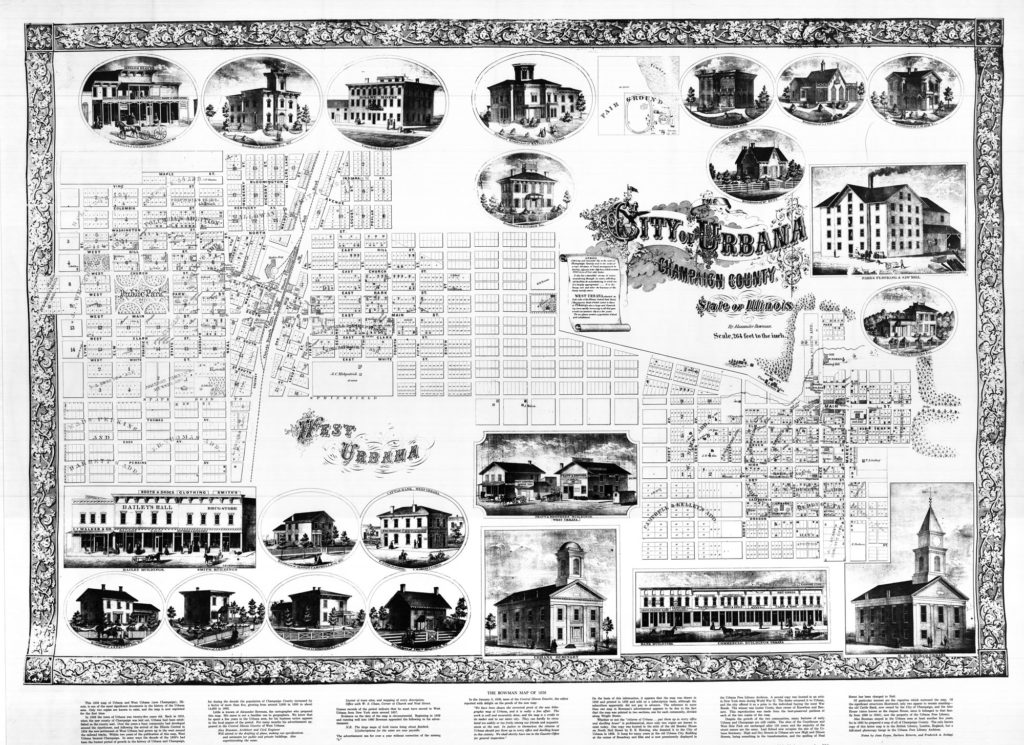

At this point, the picture becomes somewhat confusing. Beginning on March 22, 1854, several large additions were surveyed and recorded in what was to become Champaign. These did not include the Busey-railroad parcel. Curiously, in contrast with the plats, which had been recorded earlier, the Railroad Addition was oriented with the tracks, not with the cardinal directions, creating a traffic circulation nightmare for future generations.

It is reported, and probable, that the railroad surveyed and laid out the Busey tract immediately after its acquisition. However, as the plat clearly shows, it was not recorded until some two years later on June 5, 1855. This was a result of a provision in the original Illinois Central charter prohibiting the railroad from laying out towns. The restriction was rescinded on February 14, 1855, to the extent that the railroad could “layout” towns only at “such points on the (line) where their depots are already located and established.”

Led by the land speculators who were followed in turn by merchants – all anxious to exploit the commercial opportunities offered by the railroad – a settlement of sorts was in place even before the tracks reached the depot buildings. The first large plat actually recorded, well in advance of the Busey tract, was that of N.M. Clark, J.A. Farnham and J.P. White. It was about the same size as the Busey land, situated immediately to the west. The plat indicated it was “to be recorded as an addition to the town of Urbana.”

Various names had been proposed for the addition, among them “Clarksfield,” “Urbana City” and “Rantoul.” The first name would have honored one of the first speculators, the last, one of the incorporators of the Illinois Central. Rantoul was the name chosen, and for a time lots in what is today Champaign were advertised under that name in the Urbana Union by W.N. Coler, an Urbana entrepreneur and real estate salesman.

The Illinois Central, however, was not attracted to the name Rantoul for the station; it insisted upon the pre-existing name of Urbana. Accordingly, when the railroad published its schedule after its arrival on July 24, 1854, it listed its station that way. Robert Rantoul was honored after all when his name was moved to the station at Mink Grove, some 12 miles north.

For a time there was a debate over whether or not Urbana should simply pack up and move west to the tracks. Again, Cunningham:

“It might have been wiser for the little population of Urbana…to have accepted to situation, and like Homer… followed the trend of events to the railroad; but they thought and acted otherwise. They might with no great expense…have put all buildings worth removing upon runners and set them down near the depot grounds.”

There is good reason to expect that Farnham, Clark and White anticipated such a move by including in their plat a large area designated a “public square” (now West Side Park) for the possible accommodation of the courthouse or other public buildings.

Early descriptions of the area around the depot indicate why many did not wish to move there. Lothrop described the conditions as follows:

Early descriptions of the area around the depot indicate why many did not wish to move there. Lothrop described the conditions as follows:

“At this time (1854), the land now occupied by the business center of the city, was an interminable slough; from Larned’s Block, east and south-east, the land was low, wet, marshy and unpromising; especially as a site for a city. The place where Barrett’s Block now stands was a bog and all the way down Main Street, the liquid mud, in uncomfortable quantities stood or moved sluggishly along toward Boneyard Branch.”

The 1878 history was in agreement: “That portion of Champaign now occupied by business blocks was a slough and the mud was of great depth along what is now Main Street.”

On January 4, 1855, a positive approach to the developing problems created by the physical separation of Urbana and the depot was announced in the Urbana UNION.

“The citizens of Urbana, both old and new towns, are invited to meet at the Court House on Friday evening to take into consideration the subject of incorporation. Come out, one and all.”

The drive for incorporation had the support of the railroad and, as suggested by the article, the initial effort was to combine “Urbana proper and the Depot together with a large scope of county around town.”

The drive for incorporation had the support of the railroad and, as suggested by the article, the initial effort was to combine “Urbana proper and the Depot together with a large scope of county around town.”

One John Campbell went to Springfield to secure a joint charter from the legislature. According to an editorial in the January 11, 1855, Union, “much opposition exists to the measure among some of our citizens at the Depot,” which was separated from the old town by a mile and a half of wet prairie.

“The objection,” continued the editorial, “… is that the old portion of the town (Urbana), being the strongest, would monopolize the other by appropriating the public monies to the benefit of its streets while other portions were left unimproved.” Adopting a far-sighted view, the writer (possibly Cunningham) argued:

“By separate incorporations being in such close proximity to each other and jealousies would naturally arise, which would operate to the disadvantage of both, while the cost of such incorporations would be double that of one, as two sets of officers must be supported.”

“The advantages which must accrue to us from having one common interest – must be apparent to all. Instead of two little insignificant town corporations with hardly power to shut up a truant pig, we may assume the importance and authority of a city.”

Interests at the depot, however, were not passive. Residents raised a storm of opposition, sending a representative (one Mr. Pierce) to Springfield by the slow mail stage, then making two trips a week, charged with the duty of strangling the infant city.

The Union was unabashedly a booster for joint incorporation. On January 18, it published a glowing report on the depot and the values of unification.

“We notice decided marks of improvement in the direction of the Depot. Two fine two story buildings are now going up, which are to be occupied by stores, and two will soon make their appearance. Several tasty dwellings are in course of construction. Quite a change has taken place in that locality within one year. One year from this time it will contain a thousand inhabitants – our word for that. The act of incorporation, which we hope soon to get, which will unite the interests of the two points, will very much enhance the interests of both.”

Apparently the Legislature was receptive; on January 25, the Union reported:

Apparently the Legislature was receptive; on January 25, the Union reported:

“An act has passed the Legislature incorporating the “City of Urbana,” which includes both the old and new towns in one burrough. This charter, if adopted, will, we think, prove a great utility to the interests of our town. Order will come out of confusion.”

Narrowly focused self-interest, however, continued to play a significant role in the course of events. In a letter printed in the Union, the writer identified as “C” (Cunningham?), lamented:

“Is it known that any project for the public benefit is no sooner finished at all, it is after its projectors have passed away? The love of the almighty dollar seems to reign supreme in the minds of our people to the exclusion of other and better things.”

In the same issue, the editor, while optimistic, nevertheless called upon his fellow citizens to do better. He ended a commentary with a final plug for incorporation:

“We look for a time not far distant when a better state of things will exist; but at the same time would exhort our people not to wait idly the coming of such a time, but to go vigorously to work to produce reformation. Let no one consider himself excused from the work of public improvement, for every man is interested. Incorporation…shall form a basis for improvements, and the work once commenced it will go on.”

The early optimism proved somewhat premature; the opposition was effective, and the depot was not included in the charter granted to Urbana by the legislature on February 14, 1855. Printed in its entirety by the Union in its edition of March 29, the charter clearly describes the designated western boundary where Wright Street is today.

The early optimism proved somewhat premature; the opposition was effective, and the depot was not included in the charter granted to Urbana by the legislature on February 14, 1855. Printed in its entirety by the Union in its edition of March 29, the charter clearly describes the designated western boundary where Wright Street is today.

Four days later, the charter election was held in Urbana. Under the headline “Hurra (sic) for the City of Urbana: Tremendous Fight with Old Fogyism; Four Men Slain!!!,” the newspaper announced the results:

“They (the polls) were closed-ballots counted while citizens stood breathlessly waiting the result – at last it came – when it proved that the great opposition, consisted in the ballots of four sovereign votes. We will take this opportunity of saying that we will wager our hat that these same men either want to keep a whisky [sic] shop, or let their pigs fatten in the street where they have always kept their wood piles. We presume they are good fellow, if they are not ex whiskey sellers, but we advise them not to let it get out how they voted.”

In the meantime, another event occurred which reinforced the drift toward separate identities for the two towns. On March 2, 1855, a post office was established at the depot with the name “West Urbana,” presumably to distinguish it from the pre-existing post office in Urbana.

During the same period, several town plats were recorded, including that of Farnham, Clark and White, either unnamed or designated as additions to Urbana. Then, on April 27, 1855, White recorded a large, new plat immediately to the west of his earlier speculation. He labeled it an addition to “the Town of West Urbana,” apparently following the lead of the post office. Cunningham reported that the citizens of the new town “strenuously petitioned the railroad authorities” for a change of name by adding the prefix “West” to the station name.

The railroad stood fast, continuing to list the station as Urbana for more than half a decade. The position of the Illinois Central was that the station location was Urbana – and that was that.

At the end of March, the Union reported that “the citizens of the Depot have taken measures to incorporate,” but the drive failed to achieve any early success. For the most part, if one can judge from references in the Union, the locals continued to refer to the new town as “the Depot.”

Meanwhile, on May 5, a committee composed of four prominent Urbana citizens divided the City into wards for the first municipal election. On June 2, 1855, Archa Campbell became the first mayor. That same summer, a census taken in West Urbana showed a population of 416 persons.

While West Urbana failed to incorporate, civic activities were taking place. The Union reported that on January 7, 1856, the first election in the “West Urbana” precinct had occurred; 84 votes were cast electing two justices of the peace and two constables. Four months later a “prosecuting committee” appointed by West Urbana citizens “dried up the illegal traffic in ardent spirits.” Its members “performed their duty fearlessly, and a town free from doggeries is the result.”

While West Urbana failed to incorporate, civic activities were taking place. The Union reported that on January 7, 1856, the first election in the “West Urbana” precinct had occurred; 84 votes were cast electing two justices of the peace and two constables. Four months later a “prosecuting committee” appointed by West Urbana citizens “dried up the illegal traffic in ardent spirits.” Its members “performed their duty fearlessly, and a town free from doggeries is the result.”

Urbana interests realized very early the importance of the railroad. Thus, while certain citizens had successfully resisted moving the town, there seemed to be little dispute concerning the need for access to the upstart Depot. In January 1854, the Union reported that “a large number of citizens met at the Court House…for the purpose of taking into considerable measures for building a plan road from the Court House to the Depot.”

Real estate man Coler was named to the “Committee of Nine…whose duty shall be to survey the different routes and make an estimate of the probable cost of each and also ascertain the cheapest and most expeditious method of building the road.”

Over a year later, the Union noted: “The road to the Depot has lately, we are told, been materially improved by the grading and planking of certain slough (the Boneyard) which has heretofore been considered an extremely hard place.” By the summer of 1856, road conditions allowed an omnibus line that operated on an hourly schedule between Urbana and the Depot.

But the matter was still not fully resolved when, nearly two years later, the Union reprinted a long article from the Chicago Press, which dealt with both West Urbana and Urbana. In the opinion of the Press:

“A good plank road from the Depot to the Court House square is very much needed by both parts of town. This would cost but a trifle compared with the advantages to be derived from it; it would tend to do away with that jealousy which is now so apparent, and which is having a bad effect upon the interests of the whole place.”

In April 1858, the Union, after speaking well of the newly-elected trustees of West Urbana, added hopefully: “We hope they will find themselves favorable to improving the thoroughfare that connects us with them.” Seven weeks later, the Urbana Constitution provided an estimate that the road would cost $6,754. The article went on to say:

“The West Urbana Trustees, we are informed, are ready to do a liberal share, and let us see to it that men be chosen here (in Urbana), at our municipal election, who will take hold of the subject energetically and at once.”

Indicative of a good effort at improving communications, the West Urbana trustees had “ordered a sidewalk to be constructed to the eastern limit of their corporation.” The Constitution opined: “It is hoped our City Council will meet them there with a similar structure.”

Much grander approaches were undertaken to connect Urbana with the outside world. In a letter printed in the Union in January 1854, a prominent Urbanaite, T.R. Webber, announced that the legislature had granted a charter for the “Decatur and Danville Railroad Company.” Another option involved convincing the builders of the Northern Cross-Great Western Railroad, then under construction, to run the line through Monticello and Urbana. “One thing is certain,” the Union said, “a railroad will be built from the coal regions lying to the east of this vicinity to intersect at this point with the I.C.R.R. The interest of our citizens demand it.”

It was clear from the report that the degree of interest transcended mere talk. “Already,” according to the Union, “nearly seventy-thousand dollars have been subscribed by the citizenry of Urbana, and it is thought that the amount will be raised to one-hundred-thousand in a few days more.” Alas, the Great Western kept to its more direct original path between Decatur and Danville.

Three years later, still another scheme proposed a line to be called the Danville, Urbana & Bloomington Railroad. But like the Decatur, Monticello, Urbana and Danville, its time would be more than 15 years in the future.

By 1857, there was significant concern in Urbana that the new town, with the railroad, would overshadow the old. Thus in less than three years, it was Urbana, not the Depot that was on the defensive. The early fears of the new town had proven hasty and unfounded.

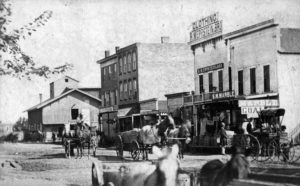

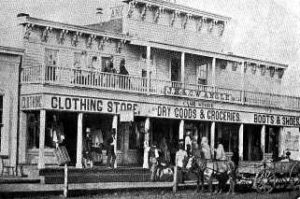

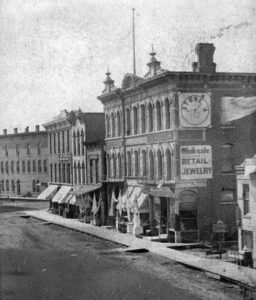

The irrefutable evidence of this, should any have been needed, was the second census of West Urbana. The population had mushroomed to 1,202 – of which 357 were between the ages of four and 21 – all accommodated in 234 homes. The first inventory of businesses indicated: 8 dry good stores, 6 lumber yards, 5 hardware and stove stores, 4 warehouses, 3 blacksmith shops, 3 millinery stores, 3 drug stores, 2 bakeries, 2 jewelers, 2 saddler shops, 2 shoe shops, 2 furniture stores, 1 flowering mill, 1 livery stable, 1 clothing store, 4 clergymen, 3 schools, 3 physicians, 2 churches, and 1 dentist.

The irrefutable evidence of this, should any have been needed, was the second census of West Urbana. The population had mushroomed to 1,202 – of which 357 were between the ages of four and 21 – all accommodated in 234 homes. The first inventory of businesses indicated: 8 dry good stores, 6 lumber yards, 5 hardware and stove stores, 4 warehouses, 3 blacksmith shops, 3 millinery stores, 3 drug stores, 2 bakeries, 2 jewelers, 2 saddler shops, 2 shoe shops, 2 furniture stores, 1 flowering mill, 1 livery stable, 1 clothing store, 4 clergymen, 3 schools, 3 physicians, 2 churches, and 1 dentist.

Also in January, 1857, the Union announced the anticipated spring opening of the Cattle Bank. Today, restored with the help of the City of Champaign, the building stands on the northeast corner of University Avenue and First Street. It is the oldest surviving commercial structure in the twin-cities.

The following April, the Union reported that the citizens of the Depot had successfully incorporated under the name “The Town of West Urbana,” and that five trustees had been elected. Rivalry, as the Union had predicted, developed quickly between the old and new towns. Cunningham later wrote:

“In the beginning of this dual existence, Urbana, with the advantage of being the county seat and with a more thorough acquaintance with the dwellers throughout the county, had, and for some time maintained, its advantage in trade; but gradually and imperceptibility the advantage of buying his supplies where he marketed his products, won the farmer, which together with a desire on the part of newly arrived citizens to be near to a railroad station, gradually sapped and finally arrested the growth and business of Urbana, and gave life and strength to its rival.”

While it appeared to be an uphill fight, Urbana interests were quick to utilize those devices at their disposal to keep the old town alive. Again, according to Cunningham:

“West Urbana grew rapidly and Urbana stood still. The work of maintaining the position taken was hard and at times, very discouraging on the part of Urbana. The members of the County Board, however, being old citizens of the county and friends of the people of Urbana, lent their aid, so far as official acts and influences would go, in the aid of the older town.”

The old town now faced a new and potentially fatal threat. Cunningham wrote that:

“(Urbana) struggled against a popular clamor from the more recent additions to the population in favor of the removal of the county seat to the new town. This came mostly from the western portion of the county and from those parts of the north and south portions contiguous to the Illinois Central Railroad.”

The climax came in the 1857 election for a county judge and the two associate justices of the peace responsible for the legislative direction of the county. According to Cunningham, West Urbana fielded three candidates for county judge “between whom a fierce war was waged.”

The climax came in the 1857 election for a county judge and the two associate justices of the peace responsible for the legislative direction of the county. According to Cunningham, West Urbana fielded three candidates for county judge “between whom a fierce war was waged.”

Urbana overwhelmingly supported one, Edward Ater. Cunningham continues: “Work was passed out to all the settlements (quietly one would presume) that (Ater) was the choice to be voted for.”

From the returns published in the Union, it would appear that there were three candidates for County Judge all together. Perhaps Cunningham meant that all three persons vied for the honor of being the favorite in West Urbana. Mark Carley, who was the favorite there, out-polled his two rivals combined in the West Urbana precinct, but received a thorough thrashing everywhere else.

The Urbana precinct, on the other hand, cast nearly twice as many votes for judge as its rival to the west. Thus, while the populations were probably close to equal, the older, established population of Urbana was much more active politically.

For West Urbana and its allies among the new arrivals to the county, the result was a disaster. Accompanying Ater on the board as associate justices of the peace were John P. Tenbrook and Lewis Jones, “old citizens and friends of Urbana.”

The new board took a decisive move to retain the county seat in Urbana. The existing courthouse, according to Cunningham, was “a fair brick building, large enough for the public demands at that time, but unsafe for the protection of public records.” The board decided to build a new courthouse – in Urbana, of course. Cunningham’s history noted:

“The expenditure of so much money would undoubtedly have the effect to make Urbana the permanent capital of the county, and many were of (the) opinion that the seat of justice should be moved to Champaign which at that time was about equal in wealth, population and influence to the older city, Urbana.”

“The authorities were friendly to Urbana, and probably thought as did the citizens of Urbana, to set at rest at once and forever the county seat question by erecting even in advance of the wants of the county, a courthouse so complete as to render another building unnecessary for many years to come, and so costly as to make it improbable that it should ever be discarded for another.”

“Local jealousies,” relates Cunningham, “were inflamed to the greatest extent ever known.” One example of the cross-town animosity occurred when Champaign editor John Scroggs of the Gazette apparently delivered a particularly vehement attack against the county board over its “expenses.” The Union, under the headline “Rule or Ruin,” tartly responded: “In his (Scroggs) last, he pitches into the executive officers of Champaign County with a vim that would do honor to a fighting cock.”

Animosity aside, the project proceeded. The Cunningham history noted that “plans for additions to the courthouse” in fact, “razed the (old) courthouse to its foundations and erected thereon a (new) fire-proof building” which was opened for public use in 1861.

Before the fruits of the county board’s labor had been accomplished, the losers in 1857 had struck back. By referendum, they overthrew the three-member county board approving in November 1859 the institution of township organization. As a consequence, the county board was expanded to 15 members, one each from the new townships.

During 1857, the growth of West Urbana abated somewhat. In a census reported in January 1858, the total population was 1,298 -up only 96 persons from a year earlier.

The larger proposals for east-west railroads had failed to offer Urbana the short-term access deemed essential for survival. Thus, promoters sought and received a charter for the Urbana Railroad Company with former Mayor Archa Campbell as president. The intention was to connect Urbana with the Illinois Central as well as with the Wabash to the southeast.

The larger proposals for east-west railroads had failed to offer Urbana the short-term access deemed essential for survival. Thus, promoters sought and received a charter for the Urbana Railroad Company with former Mayor Archa Campbell as president. The intention was to connect Urbana with the Illinois Central as well as with the Wabash to the southeast.

Undercapitalized, the venture came to a halt by the summer of 1860. In the spring of 1863, Urbana resuscitated the project by offering the assets to a New York entrepreneur who expeditiously saw the project through to the extent of linking Urbana with the Illinois Central. Cunningham described the opening event: “… on the 17th day of August, 1863, the one car – the total of the rolling stock of the corporation – propelled by a team of mules, rolled into Urbana from the West.” “The railroad,” he continued, “was north more than it cost Urbana.”

That and the new court house probably saved the city. The stone arch bridge which carried the tracks across the Boneyard survived, albeit in a most neglected condition, long enough to be restored in 1981 by the Champaign Park District. It can be seen today in the mini-park located at the comer of Springfield Avenue and Second Street.

In the meantime, following its incorporation in 1857, the village of West Urbana embarked upon its four-year experience of incorporation under the name “Village of West Urbana.” That lasted until 1861 when Champaign received its charter of incorporation as a city. From that point forward, the cities have remained like Siamese twins, separate but joined.

Unification, or re-unification, if one prefers, has been considered periodically over the years. On at least two occasions (1953 and 1980) during the past 35 years, voters have soundly rejected the idea. Will the merger question arise again? Don’t bet against it.